Part of the reason that Magic is such a successful game is that many people involved with the game—at all different levels—are aware of the importance of the game’s basic economics: If players aren’t playing the game and they aren’t buying cards, the game will cease to exist. For this reason (among others), Wizards of the Coast (WotC) has done an excellent job of supporting Local Gaming Store (LGS) participation in the tournament scene. This doesn’t mean, however, that WotC does all the work—far from it. Stores consistently are looking for new ways to attract customers and to generate interest in their products.

To this end, the Game Preserve (GP) store in Bloomington, Indiana has begun a very interesting and fun program that is designed to bring players into the store at least once per week. Through this article, I want to do two things: discuss the format used in this innovation (4-Card Blind) and briefly address how the format can be used to support your own LGS.

What is 4-Card Blind (4CB)?

4CB is a theoretical Magic format that has been played in various Magic forums over the years. I first became aware of it around 2006, but several Internet sources place its inception around 2003 in an MTG News message board. Bear in mind that 4CB is very literally a theoretical format. Players submit decklists which are then played against each other by the tournament moderators using the principle that each ‘deck’ makes the most optimal play in every circumstance (for this reason, a store interested in this program should consider getting a minimum of two experienced Magic players to run the events). The current set of rules that we use is:

Deck Construction

- A deck only consists of four cards

- Each player starts with all four cards in their hand

- Each player plays with their hand revealed; there is no hidden information

- Players draw cards but do not lose the game for being unable to draw a card

- Random effects end in the result most beneficial to the opponent of the owner of the card generating the effect

- This will be a HIGHLANDER format, meaning you can only use one copy of each card in your deck (with the exception of basic lands)

- You may use any Magic card that is not on the ban list (an evolving list—see below)

- Remember, this is a theoretical format, so you don’t actually have to own the cards nor do you actually physically play them

As we can see, this format’s popularity on message boards makes a lot of sense because it’s a fairly quick process to get a deck together, and there is no time needed to ‘play’ in the weekly event. In order to use a 4CB tournament to support the store, the GP requires that players submit decklists on a “deck registration slip” in person, at the store. This process both encourages regular Magic players to (potentially) visit the store more than they ordinarily would; it also gets both casual and competitive players interested in the format to stop by the store if they wouldn’t otherwise—and we tacitly assume that there is a positive correlation between Magic players in a store and purchases of Magic cards/sealed product from that store.

This is key: In order to encourage participation, the GP offers a small amount of store credit to the winner of each weekly tournament.

Running the Tournament

4CB tournaments are run in round-robin fashion, with each deck being paired against each other deck once per event. So if an event has 31 players, then each deck will be matched up 30 times. For each matchup, there are two games: one on the play and one on the draw.

For each match win (defined, across both games, as WW, DW, or WD), a player gets 3 points. For each draw (defined, across both games, as WL, LW, or DD), he/she gets 1 point. For each loss (defined, across both games, as LL, DL, or LD), he/she 0 points.

This is a reasonable amount of work for whoever is in charge of running the event, as the work added with each deck is multiplicative rather than additive. However, with a team working on it (i.e., via Google Docs), it goes pretty quickly.

For the example above, the best possible tournament score would be 90 (winning all 30 matches). In practice, receiving a score that high is unlikely because there is a reasonable possibility of encountering a generally bad strategy that randomly beats your deck even while losing to most other decks.

The Initial Ban List

The real fun of the format, though, is the evolving ban list. I’ve seen a variety of different ban lists when a 4CB league starts out. We used the most basic initial list, which is:

- All ante cards

- All Unglued/Unhinged cards

- All dexterity-based cards (i.e., Chaos Orb)

- Shahrazad

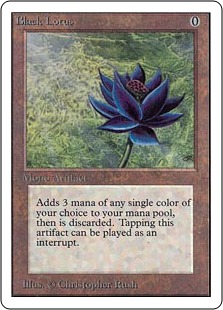

This means that for the first week (potentially more), there are a lot of very explosive decks and a lot of free spells floating around. For instance, let’s take a look at the deck that won the first week in the GP’s league.

This is a very difficult deck to beat. It will counter the first spell that an opponent plays (in 4CB, especially in the first few weeks, a Force Spike is frequently just a hard Counterspell) on the play or the draw. Left undisrupted, it will win on the first turn via Laboratory Maniac and Gitaxian Probe. It is also strong against opposing Chancellor of the Annex decks because it can burn a Gitaxian Probe (getting it countered), play a Laboratory Maniac off of a Black Lotus, and win on the following turn.

It is worth noting that when this format was ‘pioneered’ the Phyrexian mana cards didn’t exist, and neither did Laboratory Maniac, which is a one-card combo. The combination of these cards is, as we have noted, quite powerful.

When I submitted a deck for the first week, I forgot that Gitaxian Probe existed. I assumed (mistakenly) that the best deck would use Laboratory Maniac but would have additional disruption and would need to wait a turn to win.

My ‘resilient’ decklist was designed to beat Laboratory Maniac decks on the play and lose to them on the draw (forcing a draw) while beating other creature-based strategies. I tried:

This deck beats any creature-based strategy that does not use lands and does not win on turn one. It also beats any countermagic/discard that does not exile a spell.

It also got absolutely crushed in week one competition. This is the interesting component of the metagame. Many players just chose to run basic, easy-kill combos that lost to Chancellor of the Annex or Force of Will. Some of them even came very close to winning.

Almost as obvious a decklist with stars and cities in it, but it didn’t even occur to me that people would submit it. As it turns out, 16% of players did! Other players metagamed against this more obvious threat and just ran a Leyline of Sanctity and a three-card win condition.

The Evolving Ban List

There are two primary approaches that a store can take when designing a ban list. The first is to use the least restrictive ban list that is practical (as we did). In this case, the degenerate decks will probably win for the first two weeks but not necessarily because one has to do the best against the field to win, not just the best against the best decks.

The ban list, though, is evolving. Every card in the winning deck from each week is added to the ban list. In addition, though percentages chosen may vary, we ban every card that appears in 50% or more of the submitted lists in any one week.

This means that a “super strategy” involving Laboratory Maniac is only good for the first week, after which it likely will be banned.

An alternate approach is to begin with a banned list that is +1 or +2 cards from the smallest possible list (adding Laboratory Maniac or Laboratory Maniac and Chancellor of the Annex). This will increase the diversity of decks in the first round but may ruffle some feathers of 4CB spikes, should that player group exist.

The longer the tournament runs, though, the more interesting the decks become (and, in some cases, the harder it becomes to run the matchups in a timely fashion, as creature combat becomes more and more frequent).

In addition to being a fun addition to any LGS, 4CB is a good way to get players involved with the store and, more importantly, in the store. It’s also great for EDH players who are always interested in the next card to give their favorite deck an edge.

If you’re the manager or owner of an LGS, I encourage you to give this style of player engagement a try!