Welcome back to another Custom Cube filled edition of Cubers Anonymous. Last time we looked at what Ali and I had done design-wise with the Custom Cube Project. Jump back here to refresh yourself. Don’t worry, I’ll wait.

So where did we leave the story?

That’s right. Disaster. Of the complete and utter variety.

What You Don’t Know Can’t Hurt You…Right?

Were we prepared? Yes and no. Physically, we had a cube of 360 cards, sleeved and all, ready for as many eight-man drafts as we had willing bodies. Logistically, we had our ideas of all of our planned color identities and expected archetypes. Emotionally, we never could’ve anticipated the weight of 200+ little failures compounded into a massive weight sitting on your shoulders.

I barked out orders for the first few drafts, making sure everyone understood how important it was to us that it was clear they were testing our cards. I felt like I was letting someone hold my newborn baby for the first time—proud but apprehensive all rolled into one.

The first draft went about as expected. Silent reading, lots of raised eyebrows, and even more questions. Then more silent reading and raised eyebrows turned to confusion. It had to have been the longest draft I’ve ever witnessed, and not because I was anticipating what decks would come. No, it seriously took a long time. I understand that these are new cards, but come on people! All of these words are still in the English language!

Around pack three, I had learned the name of our first enemy, and its name was complexity. We had dug so deep into our designer chairs that we crammed 46 different things onto each card, thus making it novella-like in appearance. It seemed so simple in retrospect to not overdo it and start slow. Instead, we had let the ideas in our head pour out of our little fingers and fill up each card until we were satisfied that we’d fit every idea we’d ever had about what makes Magic awesome condensed into 310-ish cards.

By the end of the weekend, I’d begun to loathe the c-word. I knew we would need a massive overhaul of about 25% of the cards and some mild cleaning up of around another 25%. There was just too much going on even when folks understood all of the newness. There was just too much to keep track of. We knew there would be some memory playing considering our testers were learning new cards on the fly, but seeing as we knew the ins and out of all this newness, we had trouble grasping when someone didn’t immediately grok each card.

We had all the expected hits (misses): a card that played like Fact or Fiction and Midnight Bargain and read like the two jammed together. A planeswalker that turned creatures into Frogs, then stole the Frogs, then made Frogs better, but only could add counters when you drew cards and had card text so tiny you needed a magnifying glass. An artifact creature that gained an ability depending on the type of mana used to pay for said ability. Some cards were so text-y that you forgot what the beginning of the card said by the time you got to the end of it. And it wasn’t just cards themselves, but interactions too. There were situations where game states got so gummed up that some games turned into Magic: The Puzzling for both players just to find a way out. Unless of course one of them had an overly ambitious, undercosted piece of cardboard Power.

If someone had put the over/under of "How many games do you watch before realizing Power cards are a bad idea?" at 3.5, I would’ve taken the over and promptly donated all of my cash to the house. This was a hard but very quick pill to swallow, as we had begun to market the Custom Cube Project with the five Power cards, one in each color. Not only did they need to go, but at least two of them received the pen treatment before the weekend was through. This was a standard cube lesson we both knew but chose to ignore.

Power cards don’t really make the game more fun. Sure, they feel nice to cast, but ultimately they don’t offer interactive experiences and leave 50% of the game participants with a bad taste in their mouths. Playing with the Moxen and Black Lotus in real cubes is a little different because 1) those cards have a non-imagined place in history and 2) only accelerate your other spells and don’t snap your opponent’s back in half for just a few measly mana. We also had "fixed" Moxen that cost a colorless mana, and after one-card/two-card/red-card/no-blue cards master Eric Klug somehow drafted three faux Mox, that was about all it took.

This led us to a second, more insidious evil term: overpowered. This word is the one that still makes my lip snarl, but in this case it was right. We knew that we had initially "overpowered" several cards in the cube, with the mindset that it would be easier to start at the most powerful a card would be and go down the mountain from there. Turns out it works like a pendulum rather than a slope, but we’ll cover that in a bit.

As far as the Power, these were all the first cards that hit the bin, an easy agreement between Ali and me.

Much easier than the argument to put art on playtest cards, something Ali was entirely for and I was vehemently against. It took all of five minutes into the first draft to realize that he was 100% right. Having blank card faces only designating card color by a washed-out background and mana cost wasn’t making the cards that were filled to the brim with text any easier to digest. Full disclosure here: this was the very first time in my many years of playing Magic that I really understood the incredibly important connection between card flavor and emotional response.

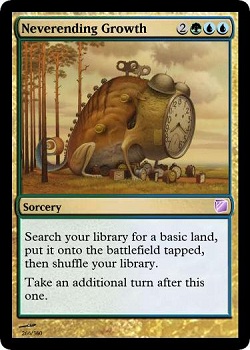

I’ve felt it before for sure—the first booster pack I ever opened was an Urza’s Legacy one, where a giant adorable Squirrel was peering over the Forests and out of the rare slot ready to give my surely terrible creature +7/+7. But twelve-year-old me was much easier to please, and I’d lost sight of that connection until I saw someone cast a card that Ali had made, particularly one with an actual name and art. It was a simple one, a pet card of his called Neverending Growth, and has remained unchanged from its first ever form.

"This card is awesome!"

There it is—THAT is the connection.

"Thanks man!" I was secretly dancing in my head.

The More Things Change…

Of course, we made things more difficult on ourselves, too. I had the bright idea of giving the reprinted cards new names, just to make sure that everything was original. I hit yet again with the insta-fails. We were just adding, yup, you guessed it, MORE COMPLEXITY for almost no reason. Out came the new names and in with the familiar. We’d take care of uniqueness with art. That was the easiest fix given all of the follies we’d racked up. Though I am being critical of our first foray, we did get some things right. In particular, we’d passed our "create color identities" test with flying colors. Everything we intended to exist did exist and was drafted at least once. They include:

The enchantment deck. Our first goal for white was to be super-concerned with artifacts and enchantments and have the ability to draft an Enchantress-style deck with lots of permanents that cared about each other. Blue would be a secondary color here, so a couple decks could bleed into the enchantment theme. We were worried before the event that people would have a hard time getting all of the pieces together for a cohesive deck, even though we felt like there were plenty to go around (***COUGH COUGH MODO CUBE STORM COUGH COUGH***). We were initially relieved to see that our fears were for naught, then watched in delighted horror as people kept assembling the doomsday machine.

The best analogy I can give you is when you’re the only one drafting Mechana Constructs in Ascension. It looked like a Constructed deck, so reigning in the power of some of those cards was another thing to add to the list of fixes. Highlights included an enchantment that let you sacrifice another enchantment to draw two cards (no activation cost) along with a creature aura that gave a dude flying and drew a card when it entered the battlefield. Oh, and it also jumped back in your hand Rancor-style when it hit the bin. Build your own Ancestral Recall! Neither of these cards exist anymore, sorry degenerates!

The combo deck. This one was eye opening—someone found the exact right combination of cards to have a near infinite combo of playing cards from his library for free. Blue was the go-to color for card filtering a raw draw, making sure you got to the pieces to need to progress towards the end game. The major pieces still exist in a corrected form, but you have to now go really deep to get them and hope you don’t die to an aggro deck, like…

Mono-black aggro! Turns out a little reach goes along way. Once we took away the restriction of "black gets terrible small creatures," we were able to hum along and give black some attackers Dark Ritual would be proud of (Mr. Dark Ritual isn’t a card in the cube, so we’ll just assume he approves from back in real Magic land.) The discard was powerful but controlled, and the evasion wasn’t just one-sided, as a handful of the best aggressive black creatures had shadow. Black also was one of the colors with tribal component, which combined nicely with the care black had for the graveyard—if you pushed too hard with the aggression into a sweeper, you most likely had use for those creatures being in your graveyard.

Green was the other color with tribal synergy, but our major theme was ramping and mana fixing. We made sure green was the overwhelmingly best way to fix your colors, which made even the lesser fixing/ramping spells quite powerful.

Red was always the simplest to implement but just as tough as each other color when it came to balance. The red aggro/burn deck was too good (Ali still contends it is) and needed a lot of minor work. Unfortunately, we learned there wasn’t such a thing as minor work when it came to balance, but again I’ll cover that in a bit.

Really, it was bittersweet. Ultimately, we probably fired off around six drafts last December the weekend of SCG Open Series: Charlotte featuring the Invitational. We succeeded in the fact that just about everyone had fun playing with the cube, but from watching rather than participating in all but one draft, we saw all of the failures as well. When you’ve put so much time into a project, so many hours and sleepless nights coming up with the next greatest idea/card/mechanic, you don’t want to let yourself down. We both knew this part was coming—where you have to look at your work in the mirror and grade it honestly. The fun wouldn’t last over multiple play sessions unless some work was put into deep enjoyment rather than adrenaline-hyped battle cruiser sessions.

It wasn’t really complete disaster, but we had a monumental amount of work in the months ahead. We had made more mistakes that we thought, but ultimately we knew that testing these 360 cards would take up the vast majority of the time in the project, even self-imposing a June deadline to have it finished. For those keeping count at home, it’s halfway through August, a full two and a half months longer than we’d anticipated. The time from last December through present day is the third part of our journey.

The Pendulum

We were fortunate that we could simply go home to Ali’s house and immediately get started following the work-filled weekend. With the names of our two enemies in mind, the first thing we did was very basic but incredibly meaningful—we separated the cards into three piles. The piles were named keep, change, and cut. We went through every single card in the cube and talked about how we felt about it, what needed to change, what succeeded and failed.

This took a few hours by itself and another few just to go in and change the file on each of the cards that weren’t in the keep pile. I don’t remember what the counts were that day for the piles, but after comparing our original spreadsheet (which has the first version of every card in it) and the final product today, I can tell you exactly 65 cards made it the entire way through without a single change (not counting cards that already existed). I think we did pretty well!

What followed that day and over the next nine months was by no means glorious work. We alternated testing at our local card shops (Cape Fear Games in Wilmington and Be There Games in Monroe), grinding out decks, drafts, and games. There is a reason you don’t hear a whole lot about Wizards testing their cards—there isn’t a whole hell of a lot to tell. There is a massive, massive time component to the testing process. It’s just a grind with games, making sure every card is performing how you want it to in relation to other cards and in relation to the specific color identity we’ve put it in and the archetypes it is drafted in.

That was the biggest distinction of our testing compared to WotC testing is that we almost always started our testing sessions with a draft. This accomplished multiple things, but the most important was keeping our testers happy. No one that has helped with this project has gotten anything more than a hearty thank you, so we needed to keep it interesting for them. The other reason was realism. Building canned decks or interjecting cards in specific packs doesn’t simulate how this product is going to be used, so by running actual drafts each time, we were able to see what type of deck each card was being drafted into in real time.

We’d watch how people evaluated specific cards or even whole strategies during a draft and were able to ask what they thought about how easy or difficult it was to get certain cards or effects. I know that at my store I saw specific players evolving with more knowledge of the cube and trying to target archetypes or even specific cards during a draft. Despite being exhausting, that part was always fun. Sometimes a whole group of people will misevaluate a card, and Ali or I had to step in and test it out ourselves. Here are a couple of examples of things that flew under the radar for much longer than they should have.

The only downside to the draft-to-test philosophy was it took some cards longer than others to get the hard look they needed. We always kept notes on cards, so even when it happened it was on our radar. Then again, sometimes when a card isn’t drafted it’s because it isn’t very good. Luckily, it didn’t take long to weed those cards out.

After each testing session, we’d report back to the other on what we saw in explicit detail. Usually this called for minor changes to cards before they were thrown back into the wild—a point of power shaved here, an additional colorless mana to this abilities activation there, and changing mana costs all over the place. The reason this was like a pendulum was because even if you work and work and work to get a card exactly how you want it to play by powering it up or down, you’ve changed the relation that card has with multiple other cards and usually those cards have to respond and changed to react. This causes a chain reaction of sorts, and it was incredibly difficult to measure how far-reaching each change was.

For example, if we have a burn spell that interacts with creatures but not players and it needs to deals one less damage, we make that change since we’ve identified it as a little too strong. Then that change makes that burn spell to similar to cost and efficiency with another burn spell, which has to change to avoid redundancy. We choose to increase its damage and casting cost, which causes it to be evaluated differently and interact with a new class of creatures. Then maybe a single creature needs another point of toughness to survive the burn spell, which causes the ability that it has to become stronger than we want in combat situations. This makes the creature better, which requires a casting cost change. Now it is on the same mana-cost line as another, generally more powerful creature…and so on and so forth. That was all from reducing a single point of damage that one spell dealt!

This was the pendulum. A card’s power went up, then back down, then up, then down, until it finally came to a rest. Even though that had to happen for around 250 cards in the very first version of the cube, those changes were "the easy part." What about when a card just had to be straight up cut and replaced with something completely different?

Dropping a new card into the card pool was like a tsunami washing over a city. We had to pay such close attention to how new cards interacted that sometimes it pulled our attention away from issues we were attempting to fix before it even existed. Oftentimes, it was just filling a hole—we needed a specific effect to exist, so we made it and plugged it in. The times that happened were much easier on us than when we cut a card and replaced it with a new, completely unique effect. Usually in those cases we’d just blatantly ask people about how that card was acting or go out of our way to watch it. The ecosystem of the CCP is very delicate and keeping everything in check wasn’t easy. Normal cards were difficult enough, but nothing compared to the majestic planeswalker card type.

Planeswalker Nightmares

Planeswalkers have by far the most moving parts of any card type. Casting cost, starting loyalty, how they gain loyalty, cost of each ability, game effect of each ability, and even the name of the card (for legendary purposes.) Rarely did we change one thing without changing another, as each change to a PW was a huge alter to the card. Unsurprisingly, not a single one of the fourteen PWs made it bell to bell in the testing process. Each one was an ecosystem in and of itself before it was even able to interact with other cards.

We knew that PWs needed to be more than just functionally right. They needed to feel right. Ever since Lorwyn, the planeswalker card type has been the most interesting, harshly judged, and, honestly, important card type in the game. I don’t just mean game play wise, but for the new direction of Magic. Everywhere you look you see Jace; each new set is judged by the new PWs it has or which ones are returning. They’re exciting in a different way than other cards. They’re in a class of their own in a way no other card type will ever be able to reach.

This is doubly important for cubes in general, as they tend to be even more powerful there than they are in Constructed Magic. These factors caused us to make absolute sure that each PW was picture perfect, right down to the name and the art. When the final CCP file is released, there won’t be any shame in admitting that the PWs were the first cards you looked for. Ali and I both love them too, so we’ve gone out of our way to make sure each one is completely awesome.

Thirteen out of fourteen ain’t bad, and luckily we only needed to completely scrap a PW and replace it with a new one a single time. (Spoiler: it was the Frog-loving PW from earlier. We both loved him dearly, but he had to go.) Below is his ultra-sweet replacement.

The new PW came pretty late into testing, but Ali did an excellent job on his first try considering the degree of difficulty that was required without causing massive changes to the cube. Even though every single ability changed in some way on that card from the first version to the one you see now, we had much more experience under our belt and made sure we nailed it down quickly so we didn’t have to spend a ton of time just putting it under the microscope. Despite our experience towards the end of the project, there was one thing we weren’t prepared for.

Time for Change

It became readily apparent when we were winding down the testing how long it really took for us to get each card right. In the early stages, we knew the majority of cards would need changes. That never was a problem since we’d see every card just about every testing session. We were very efficiently moving through, fixing problems and plugging holes. What we didn’t think about was the amount of time it would take to correct 25 or fifteen or ten cards instead of 100, and the answer to that question turned out to be "only slightly less time."

We had most everything where we wanted it to be but still needed help from people to get full testing in on such a small sample of cards. The last 10% of cards took just a little less time (in days, not hours) than the first 90%! We kept on with our draft-to-test to keep those helping us excited and managed to get through that last little bit without pulling our hair out. But dozens of sleepless nights and arguments about single points of toughness later, we have a completed project to call our own.

Thanks everyone so much for reading about our journey, and an even bigger thanks to those of you who helped along the way. This is the last full article I’m going to spend on the CCP, but sometime in the next couple weeks Ali will give you his final thoughts as well as release the Custom Cube Project for everyone to download and enjoy. Next time I’ll return back to our regularly scheduled real-world cube talk, but I hope you’ve enjoyed the last few weeks, too. Before I go, as always, a cube deck.

Yes, that is eight actual burn spells.

@JParnell1 on Twitter

Official Facebook Cube Drafting Page