Have you ever wondered how some people manage to always build a solid red beatdown deck once the spoiler of the latest set is out? How someone is able to build a working control deck at the beginning of the season when there is no established metagame? If that’s the case, today is going to be a treat for you because I’m going to talk about slot-based deckbuilding, the process these deckbuilders consciously or unconsciously use. (As you guys told me, you’d actually like to hear about it last time—thanks for the feedback by the way.)

Okay much to do, not much time, let’s jump right into the middle:

Understanding Slot-Based Deckbuilding

What do these two decks have in common?

Spells (47)

Creatures (15)

Lands (12)

Spells (33)

Sideboard

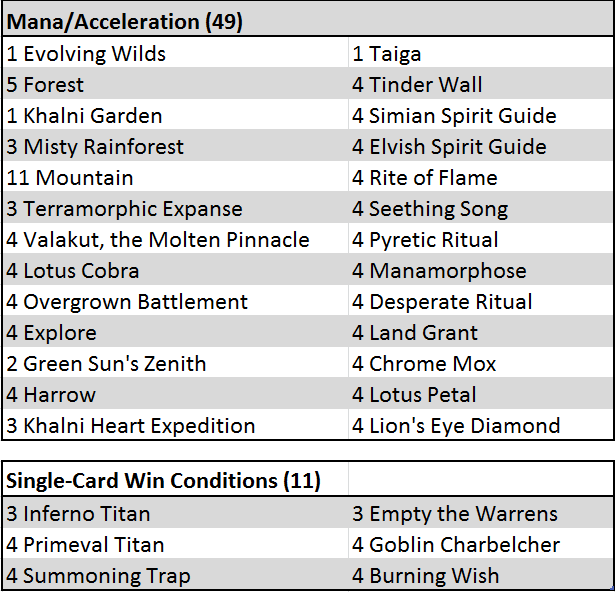

At a loss for an answer? Maybe it helps if I tell you to look at both decks’ functional subgroups (cards that essentially fill the same role being classed together—which also happens to practically be the basis for slot-based deckbuilding). Realized something? These very different looking decks are actually fundamentally the same deck!

Both are all-in combo decks that rely on consistency instead of library manipulation to find what they need. Sure, because they are from different formats and use different interactions, they look like totally different things, do very different things, and can be interacted with differently. On the level of basic functioning, though, they are the same. They both plan to ignore the opponent, produce a ton of mana (six for Valakut, seven for Belcher), and play a bomb that (hopefully) kills the other guy. What is important for us is that this is actually reflected in the decks’ structure. Check it out:

Now, you could argue that Green Sun’s Zenith in Valakut should be listed under win cons, but I suspect any early Zeniths are likely to fetch up Lotus Cobra or Overgrown Battlement, just to make sure accelerating out does work. Because of this, I’d see Zenith as primarily an acceleration spell that happens to transform into an additional bomb later—nice bonus but not the card’s primary function—an interpretation supported by the fact that there are only two Zeniths (they are fine bombs but rather weak accelerators).

Now, this kind of breakdown obviously ignores a bunch of other things, like one of these decks winning on turn 1 while the other generally needs at least four turns to get there even with a great draw, or the fact that, at some point, Valakut’s acceleration will end up moving it further towards the goal of just killing the opponent even without resolving a bomb. But when building these decks/analyzing how they were built*, these extras don’t really matter. We’re only trying to look behind the curtain and take a look at the code that forms the matrix.

In this context, something our very own Patrick Chapin (during one of the times he was sitting in the SCGLive booth) said becomes very interesting to observe: R&D couldn’t really foresee Valakut because the technology to build it—Zvi’s all-mana-acceleration and bombs Mythic deck—wasn’t known when they were future future leaguing Zendikar/M11, so nobody would have thought about a deck that is 80% mana. Turns out people in fact did, just not in the context of Standard and land-based acceleration. Well, back to the subject at hand.

This is the basic premise of slot-based deckbuilding:

Decks can be broken down into functional subgroups, which gives you a certain skeleton of slots for a certain deck type. Once you have that skeleton, you only need to fill the slots with the most appropriate cards that are available in the format you’re working with and, voila, you have a deck.

Essentially, slot-based deckbuilding is a generalized, more abstract, and more fundamental version of Frank Karsten’s approach to Faeries at Worlds 2008 that led to him playing “Average Faeries.”

Following an established skeleton doesn’t mean the deck you build will end up being good—that depends on the quality and type of the cards available in the format (for example if Valakut didn’t have Titans or something with a similar impact to work towards, you might have had a structurally sound deck but not actually a working one). It also doesn’t mean the deck wouldn’t be better with minor tweaks that depart from the skeleton depending on the exact ways the available cards function. All I’m presenting here is a very useful tool for deck development, not an automatized process that provides you with fully tuned decks.

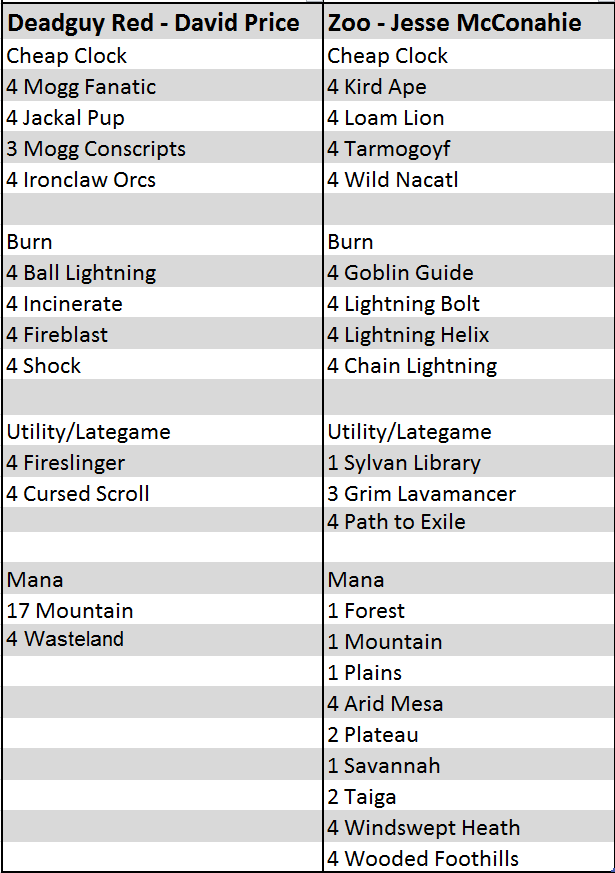

Let’s take a look at another classic example of slot-based deckbuilding (whether the designers were using the technique or not):

A decade, the use of two additional colors, and a totally different card pool lie between these two decks, and yet they are almost identical when looked at in the abstract—that is by considering cards as simply filling a desired function. Sure, the Zoo deck is running one fewer land, and Jesse’s choice for “haste creature that acts as burn” is significantly different, but both decks are structurally extremely close, the biggest differences stemming from the largely inferior creatures in Standard when Price built Deadguy Red (which both meant his guys sucked, and he didn’t need actual removal, as his burn would kill anything that came out early enough to matter anyway).

Using Slot-Based Deckbuilding

Now that you’ve hopefully understood the basic idea, let’s take a look at how you can apply this newfound knowledge. There are two basic ways to utilize this technique. The first is the obvious one of analyzing successful decks and copying their basic structure (aka their skeleton) when building something new. The second one uses this way of looking at a deck to create a new structure to base your deck on. Let’s start by using the basic approach.

To find good skeletons, you need to find good decks that do something similar to what you have in mind, break them down into their functional subgroups to expose their skeleton, and then build around this new skeleton. For this exercise let’s assume you’re like me and think Past in Flames just has to be ridiculous in Legacy. The card obviously screams Storm, so let’s take a look at one of the two best Ritual-Storm lists, Ari Lax ANT-deck.

Lands (14)

Spells (46)

- 1 Tendrils of Agony

- 4 Brainstorm

- 4 Cabal Ritual

- 4 Duress

- 3 Island

- 4 Dark Ritual

- 2 Grim Tutor

- 1 Ill-Gotten Gains

- 4 Lotus Petal

- 4 Lion's Eye Diamond

- 4 Infernal Tutor

- 4 Ponder

- 2 Thoughtseize

- 1 Ad Nauseam

- 4 Preordain

Sideboard

So let’s break this deck down into its functional subgroups:

Permanent Mana

3 Island

2 Swamp

4 Misty Rainforest

4 Polluted Delta

2 Underground Sea

2 Verdant Catacombs

Mana Acceleration

4 Lion’s Eye Diamond

4 Lotus Petal

4 Cabal Ritual

4 Dark Ritual

Disruption/Protection

4 Duress

2 Thoughtseize

Library manipulation

4 Brainstorm

4 Ponder

4 Preordain

Engine

2 Grim Tutor

4 Infernal Tutor

1 Ill-Gotten Gains

1 Ad Nauseam

Win-conditions

The first thing we realize is that the deck is incredibly clean. There is only a single slot devoted to actually killing the opponent; everything else will help the deck advance its game plan in some way shape or form. Even the deck’s engine is beautifully flexible, with two cards fueling the engine (Ad Nauseam and Ill-Gotten Gains) and the rest being tutors that are generally scripted to work as part of the engine but can also function as more library manipulation if they turn up in multiples.

The big thing that differentiates Ari’s version of the deck from the other successful version of Storm (TES) is its manabase. By running only two colors and a lot of lands (for a Legacy Storm deck), his list can play of off only basic lands and thereby largely ignore Wasteland and Daze. Assuming we aim to recreate this ability, we’ll want to limit ourselves to a two-color-deck, too.

As we’re building around Past in Flames, we obviously need to run Red. Looking above, the largest subgroup among non-mana cards is library manipulation. Because we want to copy that and almost every good library manipulation spell is blue, that commits us to being a U/R deck. So let’s fill in the slots we already know:

Permanent Mana

3 Island

2 Mountain

4 Misty Rainforest

4 Scalding Tarn

2 Volcanic Island

2 Wooded Foothills

Library manipulation

4 Brainstorm

4 Ponder

4 Preordain

In addition we know we’re going to be UR and plan on flashing back Ritual effects, so that limits a lot of our choices. The best red Ritual we have is clearly Rite of Flame, so that’s in. Seething Song simply produces more mana than the other Rituals and is therefore easier to make profitable with Past in Flames, so that’s our clear second choice. Lion’s Eye Diamond, on the other hand, can’t be reused with Past in Flames, but Black Lotus is just too powerful to ignore anyway. Lion’s Eye Diamond also has additional synergy with Past in Flames because the new red Yaggie’s Will has flashback and is therefore one of the very few cards that can effectively just be hardcast using LED mana.

So those are in, too. That leaves us with the last acceleration slot. Lotus Petal is a starter source (something that can give us the mana to start the Ritual chain) but can’t be flashed back with Past in Flames. Pyretic Ritual and Desperate Ritual, our other options, are much weaker than Lotus Petal because they don’t work as early and are much easier to Daze. At the same time, they at least do work well with Past in Flames. At this point, we can’t be sure which option is going to be better and know this is something to look out for during testing. For now let’s simply use two and two until we have more information.

Mana Acceleration

4 Rite of Flame

4 Seething Song

4 Lion’s Eye Diamond

2 Lotus Petal

2 Desperate Ritual

The Disruption/Protection package is more problematic. We don’t have access to proactive discard, so we need to choose something else. Our options are blue countermagic, a few red options, and artifacts (essentially Defense Grid). In short, our options include (obviously I might have missed something; that’s one of the difficulties with this method—you need to think of all the right cards):

Force of Will

Daze

Pact of Negation

Flusterstorm

Pyroblast (much better than Red Elemental Blast because it can be randomly cast for storm)

Red Elemental Blast

Overmaster

Defense Grid

None of these is as efficient as the Duress effects. As good as the counterspells are, we’re going to run four Lion’s Eye Diamond, with which they don’t work too well (once you crack LED, they can just counter whatever you have on the stack to use the mana with, though that is somewhat mitigated by the fact that you can punch through your Past in Flames while leaving LED’s on the board uncracked, assuming enough mana), and everything else doesn’t deal with permanent-based hate like Gaddock Teeg. For the moment, before the testing stage, I’d usually just run a wild mix so as to evaluate how each of them plays out.

Given that Overmaster seems sweet—because if it works it’s an incredible option (it also draws you a card)—and I want a list that actually looks like a real deck, I’ll focus on beating countermagic and limit myself to this:

Disruption

So now all we’re missing are an engine and a win condition. The premise was to build around Past in Flames, so those are in. To approximate the tutors, we could use Burning Wish (if we do that, we’d likely end up with only three Past in Flames in the maindeck), though in that case we really need to win with what we have in hand (we don’t have an Ad Nauseam).

Intuition would be another option, but a three-mana setup spell (our Rituals don’t cast it) seems like it might be too clunky without Manamorphose also in the deck, for which we won’t have room if we stick to the skeleton (something to try out another day).

Other than that, there’s the Brain Freeze engine. Essentially, we Brain Freeze ourselves (hopefully either after a bunch of Rituals or during the opponent’s end step after he has cooperatively produced Storm for us) so as to stock our ‘yard with Rituals and dig into a Past in Flames to flashback should we not have one yet. Once we’ve done that, we cast everything in our graveyard and flashback the Brain Freeze to deck our opponent. That engine seems sweet if only because it is similarly clean to Ari’s single win con setup, so that’s what I’ll go with for now.

One big problem with that is that it leaves us cold to opponents playing Emrakul, the best answer to which is probably running Burning Wish so as to kill with Grapeshot when necessary (and we have game 1 access to Empty the Warrens for heavy mana hands). Taking all this into consideration, I’d probably start out with this:

Engine/Win Condition

3 Brain Freeze

3 Past in Flames

3 Burning Wish

This leaves us with the following list:

Lands (12)

Spells (48)

And a sideboard that definitely contains Past in Flames, Empty the Warrens, Grapeshot, and probably the fourth Overmaster.

Some of the first things I’d be tempted to try out are Gitaxian Probe in either protection slots (if you know they don’t have FoW, you can just win) and library manipulation slots (Drawing a card for free is pretty good already, and being able to flashback it for free is gravy. It also powers up our setup Brain Freezes more easily).

I doubt this version of the deck is broken (and broken is what we’re shooting for when trying to abuse something that so resembles the Will). Actually, I know it isn’t, as it’s one of the things I tested when I worked on Past in Flames decks—the Rituals in UR are just too bad, and following the exact same skeleton as Ari’s ANT deck actually leaves you with something of a weaker version of his deck in this particular case.

I feel that this little exercise still illustrates the process you need to go through quite well, even if the result wasn’t something that just breaks the format (let me know if it doesn’t).

Slot-Based Deckbuilding—A Less Obvious Way

The above approach is a great way to establish stock lists in rather unexplored formats (like Modern or at the beginning of each Standard season)—just take the basic skeleton for red aggro, white beatdown, UW control, or green ramp, then fill the slots you know are needed with the best options available. You might not start out with the perfect version of these decks and might miss a little bit of hidden tech, but you definitely end up with something structurally sound that will allow you to judge the overall merit of the strategy in the format; you are instantly ready to start testing and tweaking. This approach also makes it easier to find a basic working skeleton for new cards that do something familiar enough that we know what type of deck we’re looking for.

There is much more that can be done by looking at a deck as a combination of functions that afterwards get filled with cards to give them substance, though. One thing I particularly like doing is to identify a particular effect that is especially powerful either in the metagame or in general and pushing that as far as possible. To do that, you identify all the basic pieces that are absolutely necessary for a deck of its type to work (using skeletons you’re familiar with) and fill every other slot with further elements that fit the function you want to push.

Both successful (measured in the results they delivered for me; nearly nobody seems to want to actually netdeck my decks) decks I’ve designed since starting to play Legacy are examples of this principle. Take a look at CAB Jace┢ and Caw Cartel and see if you can tell which element was pushed (both trademark 61-card designs, to be sure):

Planeswalkers (4)

Lands (26)

Spells (31)

Creatures (8)

Planeswalkers (5)

Lands (13)

Spells (35)

CAB Jace is from quite a bit before the Mystical Tutor ban, actually before combo took off, too. The format at that point was full of all kinds of aggro and midrange decks as well as some Standstill-based control. Against all of these, hardcore board control translates into a win quite easily, especially if it’s being used to allow you to stick a Jace, the Mind Sculptor. Being a control player, I therefore built around the Maze of Ith plan and stuck to a bare minimum of on-stack interaction. To play control, you need a minimum of card draw and library manipulation and at least a few ways to deal with non-permanent threats. Six counters is low but usually enough (freely drawn from the ancestor of control decks, Brian Weissman’s The Deck), and having fewer than eight or nine dedicated draw/filter/card-advantage options leads to a lot of inconsistency in my experience (that’s actually still quite low but compensated for by Jace being much more than just a win con). So that’s what the deck runs. Everything else is either a win con (that also happens to draw cards), a mana source, or a way to deal with the board. It’s incredibly difficult against CAB Jace to actually stick a threat and keep it around to win.

Caw Cartel approaches the game from a different angle. It tries to maximize the amount of cheap library manipulation/card advantage available to its pilot. The deck was built after I realized how ridiculous the Cantrip Cartel engine combo decks use (especially High Tide and UB ANT) actually is. You see so many cards and have so much control over your draws that it’s incredibly rare not to find the card(s) you need. At that point, my goal was to make a control deck work that could fully profit from this engine.

At the same time, while testing if Standard Caw-Blade could be ported to Legacy, I developed an unhealthy affection for the interaction between Squadron Hawk and Brainstorm, something quite ridiculous but rather inconsistent in a normal shell. Then the two ideas clicked. By surrounding Hawks with the cantrip engine, the Hawkcestral became something I could consistently set up. So this is what I did. There is a minimum of ridiculous four-mana bombs, removal, and disruption, but what is maxed out is the card-quality/advantage slots. If you’re interested in more about the genesis of this deck, check out this article (which was written before Twin-Blade was a deck, for the record).

There is a lot more I could say about these decks (for example they’re both built around the assumption that sticking a Jace will win you the game eventually and that Jace is, by and large, enough as far as win conditions are concerned), but that would lead us too far from today’s subject matter. What I wanted to show you from the example of these two decks is that this principle of identifying the most powerful or important thing for your deck to do (or simply what you really want to do) is something that makes building decks around a certain plan comparatively easy and, as you might have realized if you’ve been following my work, permeates a lot of my brewing and building.

A big advantage of this approach is that, while your decks may not be proactive by nature, they automatically are built around a particular plan, which in turn gives you direction when making in-game decisions.

Slots Filled

There is a lot more theory you can base on this slot-based approach to deck/metagame analysis, and there are a lot more applications for the whole approach in the wide world of deckbuilding, too.

At the same time, be warned, slot-based deckbuilding isn’t a be-all, end-all tool. If everybody used it, we wouldn’t ever build structurally new decks, leading to a lot of missed potential, and we should never forget that these are basic skeletons—the metagame does still play an important role in how the final product should look. Original, creative deckbuilding is far from dead just because parts of it can be understood and done by following a clear logical structure.

Sadly, there isn’t room left in this article to actually do those subjects justice, so I’ll end it here for today. If you’re interested in more deckbuilding/deck-analysis technology articles, let me know, and I’ll talk about these things somewhen in the future. I hope my slot-based approach to deckbuilding was interesting to you and will help you understand decks better, maybe even build decks more successfully.

Until next time, remember that it’s the skeleton that makes it possible to stand upright!

Carsten Kötter