Prologue: The Bar Is Raised

The Greatest Obituary of All Time

I first saw this obituary on the FinkelDraft mailing list thanks to Worth Wollpert*, but it has been making the rounds on Facebook and other social media so you might have seen it by now, as well. John Fairfax really was the most interesting man in the world (TM).

Summary (if you didn’t read):

- John Fairfax crossed the Atlantic Ocean in a rowboat, simply because it was there. Half-mad upon completion of his 180-day Atlantic rowboat journey, Fairfax declared, "This is bloody stupid," but…

- … Crossed the Pacific (also in a rowboat) only two years later. This time Fairfax took a beautiful secretary/competitive rower he had met outside London. Both later published books about the yearlong adventure, where their rowboat was damaged, they were caught in rough waters, and they were presumed lost.

- Fairfax settled his first dispute-by-pistol at age nine.

- At thirteen he ran away into the jungle and survived by trapping and skinning jaguars!

- At age 20, lovesick, he attempted to commit suicide-by-jaguar, changed his mind, and prevailed (again by pistol).

- Thereafter became a pirate’s apprentice! Apprentice!

- Escaped from the pirate ship and eventually attempted a career as a mink farmer before his oceanic voyages and eventual calling as a professional baccarat player; undoubtedly Fairfax had more adventures before…

- Dying in his seventies to leave an internationally revered obit in the paper of record.

Man, what a stud.

/ end interlude

One of the most common things that aspiring tournament players hear when trying to solicit advice on how to get better is that they should learn to make the tight play.

"Play tight!" they are told.

"… and play the best deck!"

Play tight, and play the best deck.

Simple.

Done.

Why read coverage? Why watch videos? Why bother having Premium Magic: The Gathering services? That’s it. All of tournament Magic is solved inside of six words.

But what does it even mean to "play tight(ly)?" Many players don’t know.

… And what they really don’t know is that even if they knew the tight play, and could make it all the time, every time—yes—their results would very likely improve (especially if they were also always on the best deck), but that would not suddenly transform them into Hall of Fame heartthrob two-time PT winner Brian Kibler or anything.

Today I’m going to make a case for loose play—at least loose play sometimes—that will probably be convincing. But before that, let’s open up with some working definitions.

Remember, notions of tight and loose play come to Magic primarily from poker, and have to do with how many hands a player is willing to try (loose players tend to play more), in addition to a willingness to fold versus chase pots (tight players tend not to chase). I would argue there is nothing inherently wrong with playing loose, just that most Magic pundits advocate playing tight so loose play gets the bad rap.

In Magic there isn’t really any folding (other than conceding a game, which can actually be +EV sometimes, surprisingly **), but there are predictable results. My sense is that most players think of tight as yielding predictable, if conservative, returns; whereas they think of loose as yielding potentially explosive returns, but not predictably so.

Macro:

- "Do you want fries with that?" – Will predictably earn a certain amount per hour, and with great certainty; tight.

- Winning the Mega Millions jackpot – Will potentially produce unbelievable amounts of money, but not predictably so except in extremely rare circumstances (and in those, the returns cease to be particularly exciting); loose.

So if you always play the best deck, and play super tight, you will generally have better-than-otherwise results. The reasons are simple: the best deck is usually faster or more powerful (or both) than other decks. If you do the predictable thing with a deck that is consistently better than the opponents’ decks, your improved performance should be predictably predictable.

Will you have exceptional results?

Probably not (unless no one else has the best deck). There was a time before everyone on the Open Series realized that Caw-Blade was Caw-Blade and the early adopters—your AJ Sacher or Gerry Thompson—would have a legitimate tech advantage on the rest of the room.

Later, when it started to become evident that the Caw-Blade mirror was such a skill matchup, the same kinds of results started to persist (especially given the advantage granted by byes), but for different reasons. Simply, the average Caw-Blade player might not even make the tight play on average, ceding tremendous percentage to those who could exploit both principles.

In order to achieve actually exceptional results, the kind that not only produce Hall of Fame careers but even just predicable performances at any tournament level, you have to deviate somewhere.

Most high-level strategy writers agree that playing the right deck is the most leverage-able way to improve your results. And most of the actual best strategists agree that the "deck to beat" is rarely the mathematically best deck to play (though that’s certainly not always the case)…which is actually the opposite of what most players in general seem to think. Instead I’m going to focus on the other half today:

Consistently tight play is probably overrated.

That’s not to say that you shouldn’t play tight… In fact, I think that most of the time conventional wisdom is correct: you should in fact strive to play tightly unless you have a good reason not to. But if you don’t deviate—and identify when to deviate—you’re going to unnecessarily limit your potential results, or worse yet, passively and intentionally sink your own rowboat.

That said, I would prefer—if you plan to go around telling everyone that Mike Flores told you to play loose—that you do so strategically. That is, you think about what you’re doing and make your loose play calculated (at least to the extent that you’re able); that is, you have a good reason for it.

Interlude: The First (and Second) Stupid Things I Did on Purpose

Part 1 – This was the game I played for my first Blue Envelope. I handily took the first game in the Necropotence vs. U/W CounterPost matchup match, but got locked down by triple Kjeldoran Outpost plus Circle of Protection: Black in the second, with ample mana and Browse ensured he could Force of Will any chances I had of getting out of it.

In my tournament report I said, "I will either be the biggest Magic genius or the biggest Magic fool," for the decision I made (remember, this was one game for the Blue Envelope and a plane ticket). I sided out most of my creatures under the theory that one Circle of Protection: Black was going to K.O. every creature anyway. I just tried to maximize my chances of getting a god-draw, so I sided in every land destruction card and color-hoser in my sideboard. I ended up getting that god-draw and killing him with (I think) one pump Order.

Part 2 – At the Pro Tour this fed I was up against Aaron Muranaka in the 0-1 bracket. Similar situation… I was playing Necropotence again and Aaron had my creatures locked down; this time I was staring down Serrated Arrows (basically a three-for-one against me) and chances of my winning by creatures was dwindling around zero. So I did something that was fairly talked about then, but became old hat later (when we all figured out how good it actually might be): I played Demonic Consultation for the one Drain Life in my deck and killed him.

Look at these two decisions. Both of them had high likelihoods of going the wrong way. How are you supposed to consistently win when you have only six 2/x ways to kill the other guy in your deck?

There’s no way to reproduce the math of the Muranaka match, but believe you me, few if any Magic: The Gathering players were willing to Consult for a one-of in 1996. People were still talking about Mark Justice decking himself in the finals of the World Championships, and if things had gone wrong? Who wants to be the idiot who Consulted himself to death? Prototype PTQ-winning scrub.

These two situations had something very much in common: if I played to the status quo…headlong into a Circle of Protection: Black in a format without Nevinyrral’s Disk as a get out of jail free card and three years before the first Duress variant or let Aaron slowly take control of the game… Both would yield losses (worst-case scenario[s]) if everything went according to plan (the other guy’s plan). However, by doing something a little different, a little bit "loose" (certainly less predictable), I might possibly produce any other result…which is exactly what I wanted.

/ end interlude.

What does the smartest guy ever think?

No, not Zvi Mowshowitz! (for once)

"Insanity: doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results."-Albert Einstein

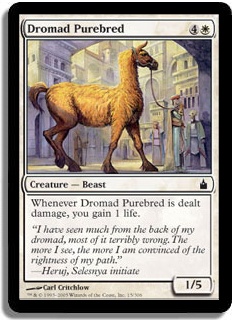

This is why consistently tight play might be a tad overrated: doing the tight thing when you have some kind of advantage is usually going to hold the advantage; but doing the tight thing in a situation where you can predict a loss…is going to give you exactly the opposite result from what you actually want. And you can see it coming. When you start thinking about matters this way, Limited five-drops like Lost in the Woods and Dromad Purebred start taking on a different light.

How about some different smart/stupidly impressive guys?

Why do we bother reading—and sharing—obituaries about men like Fairfax? Why do they get mentioned anywhere? For our purpose… What is the difference between Jon Finkel and Kai Budde?

A bunch of us were sitting around one day*** and trying to figure out what the difference between Jon’s play and Kai’s play is. I like to say Jon is the best ever because in my experience he has the most impressive process and strategies; but—not taking anything away from Jon—I think Kai is the more approachable for almost any other player. That is you can copy Kai’s preparation much more easily than you can reproduce Jon’s computer-like brain. All the original elite players (Kai, Jon, Bob, Dirk) claim they would at their heights all make the same play over 80% of the time. As if on cue, Randy would chuckle and say, "And when Jon deviates, it’s because he has the better read."

That doesn’t mean any of them will be right 100% of the time; it simply means that they will make the same plays most of the time.

So if that is the case, what’s the difference between one and the other? Is it repetitions? Tech? Dumb luck?

I think it is mostly Dromad Purebred.

In his first year with a Hall of Fame invitation, Jon played in a Ravnica Limited PT (and didn’t do particularly memorably). He followed up with the OMS brothers using the same 225 as myself, Paul Jordan, and Steve Sadin; my team did substantially better than his and consequently many a Magic pundit declared Jon (and probably the whole of the HoF for all time) officially over the hill.

… And then Kuala Lampur happened.

That said, I think the crux of Jon’s difference that makes the difference can be gleaned by that first Ravnica Block PT. By his own chuckling admission, Jon considered himself much better prepared for the Ravnica Block PT than the Lorwyn one he won, final standings be damned. He identified himself in a troublesome matchup that he didn’t think he could win on the merits and sided in Dromad Purebred.

"Kai would never have sided in that Dromad Purebred," BDM would later comment.

How good is Dromad Purebred? About as good as it looks, which is to say, in a high impact multicolored power card format like Ravnica, not particularly good. But here’s the thing that most players will never learn over the courses of their careers as Magic players (or in life):

If all your baseline strategy is going to do is lose you the game, then doing something else—even something that will get you laughed at by lesser players—is the only thing you can do to win.

Most people fail to do interesting, exciting things with their lives or win close games of Magic: The Gathering for one simple reason: they are afraid of being ridiculed. What do you think Fairfax’s mommy said when he told her he planned to cross the icy Atlantic in a g-d rowboat? And then again two years later? With a pretty secretary? The whole thing would seem positively trite if it didn’t involve a madman crossing the ocean in a g-d rowboat. I’m sure Fairfax’s compatriots were all clapping him on the back after the jaguar incident… But what about going into the jungle to begin with? And over a girl?

These results can’t be easily—tightly—predicted… But they are the exact drivers of such memorable results.

Most players would never have sided in the Dromad Purebred because they would be afraid of someone they knew walking by, seeing a Dromad Purebred in play, and giving them beats for the rest of the day ("I guess you couldn’t find twenty-three playables, LOL!"). Even worse, if they were a someone-someone, they might be afraid of someone else writing about or promulgating to a wide audience the choice to run a Dromad Purebred.

And yet, here we are, years later, talking about the greatest player of all time fearlessly doing just that.

By the way, Jon didn’t win that match.

I have no idea if Jeremy Neeman won the time he went Lost in the Woods but it hardly matters; there’s a reason everyone who’s anyone has him on the short list of players to watch. Personally I found the whole thing ingenious, and the certainty of playing Lost in the Woods on turn five absolutely bravura.

How about my own small touch points with the dark side? The first time I won the one game all day that mattered and earned my first trip to the Pro Tour; the second time, it was my first win on the Pro Tour…and against someone who would become a longtime friend, who was coming off a PT Top 4 at the time!

I talk a lot about results; in general, I think one of the most admirable things we can do is determine the strategies that help us consistently produce the best results we can. At the same time, being "results oriented" gets a bad rap in Magic and often for good reason. In personal conversation I like to clarify with "results justified" because I think we can all agree that we should be focused on getting great results but the fallacy comes from justifying bad behavior with a positive result. Measuring the validity of the Dromad Purebred, Lost in the Woods, or Consultation for Drain Life solely on whether or not it/they produced a single game win is the height (rather nadir) of bad results-focused thinking.

Rather, the best thing we can do as writers, analysts, and (hopefully positive) influencers is shed light on new, different, and productive ways of thinking that can help produce positive results in the future. Ultimately, anything we might choose strategically—generally tight play, generally loose play, weird cards to side in, unusual or off-label implementations of otherwise acceptable cards—are all just tools. I think the best players have a wide array of tools to choose from and choose appropriately for the situations that come up. Less successful players don’t know that some of these tools exist yet and end up ridiculing them primarily out of ignorance, because their vocabularies are limited to the tools they do know.

Epilogue on Results Oriented Thinking:

One big tournament I was semi-fuming. I had been X-0 and selected for a feature match. I made what looked like a risky play, but only if you didn’t know the math. My play would win me the game on the spot (but it would take seven turns to pan out and look close, though it would never be) about 65% of the time; to the casual observer it would look like stuff was going on, but none of that stuff would matter unless I made an egregious mistake. The same would lose me the game actually on the spot the other 35% of the time and it wouldn’t look close; it would look like I had made a mistake. Alternatively, I could have set myself up for an attrition fight that I was almost certain to lose, as I already knew that my opponent had both the rocks and a hand full of interaction. It was all about mana and it was all about now. There is a story because he ended up topdecking and killing me the next turn.

A passing-by Patrick Sullivan asked me why I was talking to myself, not fuming, but definitely not at 100%. I lost? Hold on! Did I actually care about the outcome of some random game of Magic? "No," I responded, "but I am pretty sure the sideline reporters had no idea what was actually going on in that game… All they probably know is that I lost." If you know PSulli, his response will make all the sense in the world:

"Why in the world would you care what some chuckleheads say about you?"

/ act drop.

LOVE

MIKE

* #humblebrags

** I learned this from Brian Hacker back in the day. His opponent played some kind of annoying utility creature on an early turn (some kind of healer if I recall); the blue-haired phenom looked at the board, looked at his hand, and packed it in. It turns out Hacker only had one Path of Peace in his deck for removal main deck, and he didn’t want to waste the human effort—or time—trying to take the first game. Hacker told me that he thought his chances of winning game one were remote, but that it would take him 40 minutes to either win or lose. If he in fact took forever to lose game one, he might be giving himself a best-case scenario of a draw even if he won game two. Hacker actually increased his chances of winning by conceding the first game, leaving time to potentially win a game three.

*** Savage lies. This same conversation has come up easily twenty times, all involving multiple super well known Magic commentators.