Anyone who has followed my Magic career knows that I’m the kind of guy who likes attacking with green creatures. That’s nothing new. The very first deck I ever built was full of nothing but Llanowar Elves, Wild Growths, Craw Wurms, and Forests. Some things never change, I suppose.

But some things do. For a long time in Magic’s lifespan, green creatures had it pretty rough. These days we see the likes of Knight of the Reliquary, Huntmaster of the Fells, Primeval Titan, and friends making their presence felt in a big way across formats, but it hasn’t always been that way. Those green decks that made it to the winner’s circle in the dark times of Magic’s past tended to do so on the back of an impressive supporting cast of spells rather than thanks to the creatures themselves.

White didn’t have it much better. White was framed largely as a defensive color early in Magic’s history, and it’s hard to win games just by defending yourself. As Mark Rosewater put it in an old article about designing cycles, "The most famous of all cycles, the Alpha "boons" were an attempt to define the colors. Blue was defined as insanely powerful, and white was defined as timid. Ten years later, we’re still working on that."

Since it’s Selesnya Week and I am an ardent Selesnya supporter—representing the guild not only on the Planeswalker Points site but also in both Prereleases I played in—I’m going to take a look back through the lens of history and showcase those G/W decks that made an impact. Keep in mind that I’m only going to be looking at true G/W decks—not Naya decks, or Bant decks, or Jund decks (even from the days before those terms existed), but real Selesnya decks. Green and white may have been an unappreciated color pair for much of Magic’s existence, but despite that it managed to make its presence felt.

Magic has a long history, and I’ve been around for pretty much all of it. I found while writing this that I have far more to say about the history of G/W decks than I could reasonably hope to express in a single article, so I’ve decided to break up my retrospective into two parts. This first part will discuss the truly historical G/W decks, those that date back to the earliest days of the Pro Tour. The second part will cover the more modern history of the color combination. I figured a logical break point would be the same one Wizards uses to determine what cards are legal in Modern, so this part will feature decks leading up to Mirrodin block (the first set using the new card frame), while part two will cover decks from Mirrodin to the present.

Without further ado—the history of Selesnya through the lens of tournament decks!

ErhnamGeddon

Creatures (10)

Lands (22)

Spells (28)

The very first Pro Tour was won by Michael Loconto from Massachusetts playing a 62-card U/W Millstone deck, but his was not an easy road to victory. In the finals Loconto met Bertrand Lestree, one of the most notorious players coming into the event. Bertrand was best known for having allegedly punched out a judge after a heated argument (rules enforcement in those days was somewhat lax, to say the least), but he was also the finalist in the very first World Championships, where he lost to Zak Dolan.

It was no coincidence that two decks featuring white met in the finals. One of the most important cards in Standard (then called Type 2) at the time was Land Tax. Land Tax was only recently unbanned in Legacy, so you can imagine what a nightmare it must have been when it was legal in Standard. The way many games went back then was that one player would play a first turn Land Tax and the other player would refuse to play extra land to turn it on, so the two would end up in a staring contest with no clear end in sight.

Modern day Standard decks tend to be light on removal effects for card types other than creatures, but with Land Tax being one of the most dominant cards in the format, virtually every white deck of that era played four maindeck Disenchants. Shawn "Hammer" Regnier, who was also in the Top 8 of that Pro Tour (where he lost to Lestree) liked to call playing Disenchants "keeping it honest" since there were so many things you might need an answer to. Disenchant was one of the most common ways for a Land Tax stalemate to end.

The other major way was for one player to realize that they had to break it or they were going to fall behind. The ability to force the issue with Land Tax was one of G/W ErhnamGeddon’s strengths. Thanks to Brushland and mana creatures, G/W could open with a Birds of Paradise or Llanowar Elves and follow up with Land Tax, putting the opponent in the unfortunate position of having to either let the G/W player Land Tax for free or fall significantly behind on the board while waiting for a Disenchant.

And letting ErnhamGeddon Land Tax was substantially more dangerous than many other decks. While U/W decks would generally just Land Tax to thin out their decks and improve card quality, discarding their excess lands, ErhnamGeddon was able to deploy cheap creatures onto the board fast enough that their hands were rarely overflowing. And they had use for those extra lands because at any moment the world could blow up and they’d need to reload.

That was the card that really made ErhnamGeddon stand out and defined the way the deck played: Armageddon. Llanowar Elves and Birds of Paradise—plus the occasional mana artifacts like Felwar Stone, as seen in Lestree’s list—both accelerated into the devastating sorcery and provided mana sources after it resolved. It may seem strange to want to "accelerate" into a mass land destruction spell, but in a world full of Wrath of Gods, it was frequently important to take out your opponent’s mana base before they killed all of yours. The value of resolving an early Armageddon was magnified by the fact that Strip Mine was not only legal but unrestricted! Blowing up all of your opponent’s lands once could frequently mean you could keep them stuck on no more than one mana long enough for just about any creature to get the job done.

As I said in the intro, creatures have come a long way since Magic’s early days. It’s telling that Erhnam Djinn, once the gold standard for a quality creature (to the point that George Baxter splashed green for them in his own Pro Tour Top 8 deck), would be absolutely unplayable today. A four mana 4/5 with a drawback? Give me a break! But it was the best we had back then to the point that it was the namesake creature for what was the first really successful deck of the Selesnya guild: ErhnamGeddon.

Prison

Creatures (1)

Lands (23)

Spells (37)

- 2 Armageddon

- 2 Wrath of God

- 4 Swords to Plowshares

- 4 Icy Manipulator

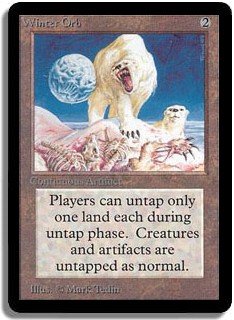

- 3 Winter Orb

- 1 Sylvan Library

- 1 Land Tax

- 1 Balance

- 2 Titania's Song

- 4 Fellwar Stone

- 2 Disenchant

- 1 Black Vise

- 3 Divine Offering

- 4 Serrated Arrows

- 3 Aeolipile

Sideboard

While the first Pro Tour may have been largely defined by controlling white decks, they did not last long at the top. The success of Necropotence decks in the hands of quarterfinalist Leon Lindback and Juniors champion Graham Tatomer spread to the world at large, and soon the world was awash with Necro decks. That period has come to be referred to as "Black Summer" due to the dominance of the Necropotence strategy during that time.

Players looked high and low for answers to Necro, but few succeeded. Come time for the US National Championships in 1996, many players were certain that Necro would dominate the event. A few savvy players caught them by surprise with unexpected strategies. One of those strategies was TurboStasis, the Howling Mine fueled lockdown deck that put future Pro Tour champions Mike Long and Matt Place on the National Team. The other was George Baxter’s Prison deck.

George Baxter was one of the first big names in Magic strategy, penning books on the subject before strategy websites on the internet were really a thing. I actually owned a number of books personally and for many years used the notation of "pockets" that he espoused when writing down my own decklists. If you can track down copies of his old books—Deep Magic is one that I remember being a favorite of mine—they’re well worth a read, if only for a glimpse into Magic history.

Baxter showed up to Nationals that year with a deck that was well positioned not only against Necro but against the very TurboStasis decks that were built to prey upon the Necro decks. Much like the ErnhamGeddon deck, Baxter’s deck was built around the power of mana denial. While he didn’t play the full four copies of Armageddon, he did play three Winter Orbs. Between Armageddon and Winter Orb, he was able to deprive the Necropotence decks of their ability to utilize the large quantities of cards they were drawing and keep them from casting the big Drain Lifes they needed to keep their engine going. Baxter could use his four Icy Manipulators to tap down either his opponent’s lands to keep them pinned down under his mana lock (hence the name "Prison") or tap his own Winter Orb during his opponent’s end step to give himself full access to his mana.

On top of that, Baxter’s five enchantment/artifact removal effects—three Divine Offerings and two Disenchants—gave him excellent protection against the Nevinyrral’s Disks that the Necro decks relied on to handle troublesome artifacts and enchantments. They also served to destroy the Howling Mines that the Stasis decks desperately needed to keep their namesake enchantments fueled with Islands. He even had a trio of Serra Angels in his sideboard that were absolutely devastating against TurboStasis, since the fact that they didn’t tap to attack (this was before the term "vigilance") meant that Stasis did nothing to keep them from ending the game in a few short turns. Serra Angel as super-secret sideboard tech? This really was the dawn of time!

The most exciting part of Baxter’s deck, though—and pretty much the only reason he was playing green—was Titania’s Song. One issue for a deck like this is actually winning the game. While Baxter also had a single copy of Deadly Insect, his primary win condition (besides boring his opponent to death) was to lock down his opponent under Winter Orb and Icy Manipulator, play out a bunch of mana artifacts and Serrated Arrows and the like, and then play Titania’s Song to kill his opponent in one fell swoop.

The bizarre Antiquities enchantment (which was for some reason reprinted—there were very different criteria for what cards made it into base sets back then) not only turned his lockdown tools into an army of angry Fae queen-inspired creatures but also turned off the effects of artifacts while in play. This was quite convenient in a world of Nevinyrral’s Disks which entered play tapped—Baxter could just play out a Titania’s Song if he didn’t have a way to kill an opposing Disk and his opponent would be left with a 4/4 creature rather than a card threatening to blow up his entire board.

Not quite the green/white decks we’ve come to know and love these days, is it? It was a different world back then. Don’t worry—it gets better.

The Striped Bears Deck

Spells (13)

- 4 Abeyance

- 2 Disenchant

- 4 Pacifism

- 3 Tithe

Mike Turian made a name for himself during his Pro Tour career as a Limited specialist, but his first success came in Constructed. Mike made Top 8 of Grand Prix Toronto back in 1997 playing this work of art. The format was Mirage/Visions/Weatherlight Constructed, and the major decks in the format going into the event were mostly black-based removal decks thanks to the power of Nekrataal. Mike’s deck attacked the format in a very unusual way, playing a suite of creatures that many would dismiss as unplayable to great effect.

Look at that lineup! No, this wasn’t a Limited tournament—that’s actually a Giant Spider in Constructed. Mike’s deck had a full EIGHT 2/2 creatures for four mana between Striped Bears and Mistmoon Griffin, but all of them provided excellent value. He could shrug off opposing Nekrataals because there was always more where that came from and ultimately play the amusingly devastating Scalebane’s Elite as his trump. In a world jam packed with heavy black decks, a Durkwood Boars with protection from black was an absolute monster.

Mike’s sideboard has unfortunately been lost to time, but I know for a fact that he came prepared for opposing control decks with the counterspell-hosing City of Solitude because he played it against me! I was actually Mike’s opponent in the quarterfinals of GP Toronto those fifteen years ago, and I managed to dispatch his array of honest green creatures with my mono-blue deck featuring Ophidian, bounce spells, control magic, and creature removal effects. I suppose I was a traitor to Selesnya for a little while…

Mulch-Oath

Spells (32)

The stories everyone remembers from the US National Championships in 1998 pretty much all involve Mike Long. There was the notorious incident where Mike was caught with a Cadaverous Bloom in his lap while shuffling up for a match with the namesake combo deck and only received a game loss penalty; he went on to make the Top 8 of the tournament. He made it all the way to the finals, in fact, where he faced a young kid named Matt Linde, who in pre-match interviews talked about how he tested for "nearly four hours" for the tournament as if that was some astronomical amount of time.

Mike was clearly Magic’s villain at this point, and everyone was rooting for Linde to win. When Mike cast Natural Balance to try to finish comboing off with Linde virtually locked under Gloom, Linde used the extra land he fetched up to cast Abeyance, stopping Mike’s ability to combo and leaving him dead to Linde’s creatures next turn. It was the first time I’d actually seen a crowd at a Magic event erupt into applause—so loud that the players could clearly hear it despite being sequestered for their match in another area of the convention center.

That’s not the story of this deck, though. This is the deck Randy Buehler played in that tournament and went 5-1 in the Constructed portion but fell short of the elimination rounds thanks to a poor showing in Draft. There are many decks that post solid records in a single event—what makes this one special? Simple: Oath of Druids. Oath of Druids was released in the Exodus expansion in June of 1998, so the US Nationals in July was one of the first opportunities anyone had to see the card in action. Oath made some waves in the US Open events—the single elimination qualifiers run immediately before Nationals, known as the "meatgrinders"—in a U/G form designed at least in part by Adrian Sullivan, but Randy’s deck was one of the first to take the card to the extremes.

Many of the Oath decks at the time ran a large complement of "Spikes," like Spike Feeder, which they could Oath into and then sacrifice to continue Oathing. Randy’s deck contained only a single Archangel, so every time he Oathed he was guaranteed to put a 5/5 vigilance flier into play. Again, newer players must be thinking: Archangel? Really? When Archangel came back in Avacyn Restored, it was only a passable Draft card in a narrow range of decks, and here we have a deck that can pick absolutely any creature it wants to put into play of any cost. This is the best it can do? Times have changed, friends.

The real core of Randy’s deck wasn’t even Oath of Druids, though, but Scroll Rack. The Mulch / Scroll Rack engine allowed Randy to massively out resource his opponents, grinding them down with repeated mass removal spells like Wrath of God and Cataclysm and all the while generating huge amounts of card advantage and card selection for himself. Gerrard’s Wisdom gave him enormous staying power against the mono-red burn decks that were popular at the time (and which Jon Finkel himself piloted to a Top 4 finish in that very tournament), and Gaea’s Blessing ensured that not only that Randy never get decked but that he could also never run out of any of the effects that he needed. Against control he could recycle Cataclysms or Armageddons, against creatures he could recycle Wrath of God, and against burn he could recycle Gerrard’s Wisdom, and the Scroll Rack / Mulch engine meant that he could find it all in no time.

So basically another grindy, lockdown, resource denial deck. Fun times with the Selesnya guild, eh? Well, thankfully, the last deck we’re going to look at today is much more in line with what G/W decks do today.

G/W Ramp

Creatures (26)

- 4 Exalted Angel

- 3 Silvos, Rogue Elemental

- 4 Ravenous Baloth

- 3 Windborn Muse

- 2 Akroma, Angel of Wrath

- 2 Daru Sanctifier

- 4 Wirewood Elf

- 4 Wall of Mulch

Lands (12)

Spells (22)

Sideboard

For those of you who read my article last week, this deck probably looks familiar. In fact, the following text is probably going to look pretty familiar, too, since it’s what I said about the deck last week!

Onslaught Block Constructed was an interesting format, defined partially by the tribal mechanics that were pushed in the block, particularly goblins, and partially by the cycling trigger enchantment pair of Lightning Rift and Astral Slide. Those two decks battling it out served as the bulk of most group’s playtesting, with the occasional foray into a Patriarch’s Bidding deck. One hidden gem in the format, however, was Explosive Vegetation.

I tested for that tournament primarily with Ben Rubin and Eric Froehlich, and we identified pretty early on that Astral Slide and Goblins would be the two main players. We also quickly identified the power of Explosive Vegetation, a four casting cost sorcery that searched for two basic lands. Explosive Vegetation made lots of things possible that were otherwise a pipe dream, like casting the powerful pit fighter legends in time for them to make an impact on the game before you died. Or even more powerful things, like the truly board dominating Akroma, Angel of Wrath.

We tested and tuned various Explosive Vegetation decks and ultimately came to pairing green with white, in part for the power of Akroma but mostly for her Vengeance. Akroma’s Vengeance was an extremely powerful tool at wiping clear the Lightning Rifts and Astral Slides that the cycling decks needed to operate as well as killing hordes of Goblins.

It was particularly important that, unlike Wrath of God, Akroma’s Vengeance didn’t have the "creatures can’t regenerate" clause, because that let us play big poppa Silvos, Rogue Elemental. We realized that the field would be primarily Goblin decks and Slide decks, neither of which could effectively actually remove Silvos permanently. Explosive Vegetation into Silvos let us hit for eight and then wipe the board clear with Vengeance—clear except for our Rogue Elemental, who could conveniently regenerate. Everything in the deck was either a big effect, a ramp effect, or some way to buy time to get to the late game where the big spells could take over: the original ramp strategy. Â

William "Baby Huey" Jensen played the deck to a Top 4 finish at PT Venice, where he lost to eventual champion Osyp Lebedowich. It’s interesting to note that the match between Huey and Osyp went a long way toward convincing the powers that be to change the rules regarding legendary creatures. For most of Magic’s history, the rule was that if there was already a legend in play and someone played another legend of the same name, the newly played legend died but the original lived.

In the match between Huey and Osyp, Huey used Oblation during Osyp’s attack step to remove an Akroma, Angel of Wrath with his own Akroma in hand. After shuffling his Angel in and drawing from the Oblation, Osyp drew that very same Akroma and played it again, stranding Huey’s own Angel in his hand and leaving him to die a terrible death. It was not long thereafter that the rule was changed so that playing a second legend killed both copies—a rule that to this day has miserable interactions with Clone effects (good riddance, Phantasmal Image, enemy of Thrun) but at least prevents anyone else from having to suffer Huey’s fate in that match.

That’s it for this week. If you think I missed any truly definitive and groundbreaking decks, please let me know in the comments. Remember, this is only Part 1—I’ll be back soon with Part 2, which will feature decks from Mirrodin onward including Astral Slide, Ghazi-Glare, Maverick, and more. I hope you enjoyed this look back at Magic’s history—I know I always enjoy writing these kinds of articles, which is probably why I get a bit carried away with them.

Until next time,

bmk

www.facebook.com/briankiblermtg

|

We are Selesnya. Whatever we need to do can be done with creatures. Knight of the Reliquary, Qasali Pridemage, Thalia, and friends don’t flinch in the face of any opposition. Together we will conquer. |